What India is Getting Right in Climate Action

India's villages are becoming unlikely climate leaders, with communities eager to adopt new tools, practices. For to scale, this needs macro-level emission cuts, policy support, and patient capital.

Bill Gates has just announced that he’s giving away all his wealth - $200 billion over the next 20 years - through the Gates Foundation. He says he’s excited about the pipeline of innovation to help children everywhere.

Melinda Gates, in her book ‘The Moment of Life’, documents the impact the Foundation brought in years ago in places like Uttar Pradesh; the north Indian state was in 2010 “called the global epicentre” of newborn and maternal deaths, with a tenth of the global three million deaths occurring there. Globally, of all the deaths in the first month, the greatest number occur on the first day, she points out in her book.

The rate declined by 37% in a decade, largely due to institutional delivery and newborn care. The Gates Foundation was among those that supported and initiated programmes to train women in life-saving skills during deliveries.

Such changes were seemingly small, like having a trained healthcare worker present at the time of birth, initiating breastfeeding within hours, and providing body warmth for a newborn suffering from hypothermia, but they have had a big impact, as the numbers show.

Climate action is paying off

Today, there’s a quiet revolution of similar, seemingly small changes and innovations that are positively impacting communities, many underprivileged. If scaled, these interventions can be beneficial for the country and planet.

Having encountered several examples and seen some firsthand over the past year, this piece is a sampling of the change that’s happening in the development sector.

It’s a sign of climate action that India is getting right at the grassroots.

While some parallels to the startup hustle of the glitzy, headline-grabbing Silicon Valleys can be seen here, what’s in short supply is long-term, flexible, risk-tolerant capital.

Solarisation of the health sector

One of the most prominent examples of scaling in recent years has been the solarisation of India’s primary health centres. Each PHC serves a population of about 20-30,000 people.

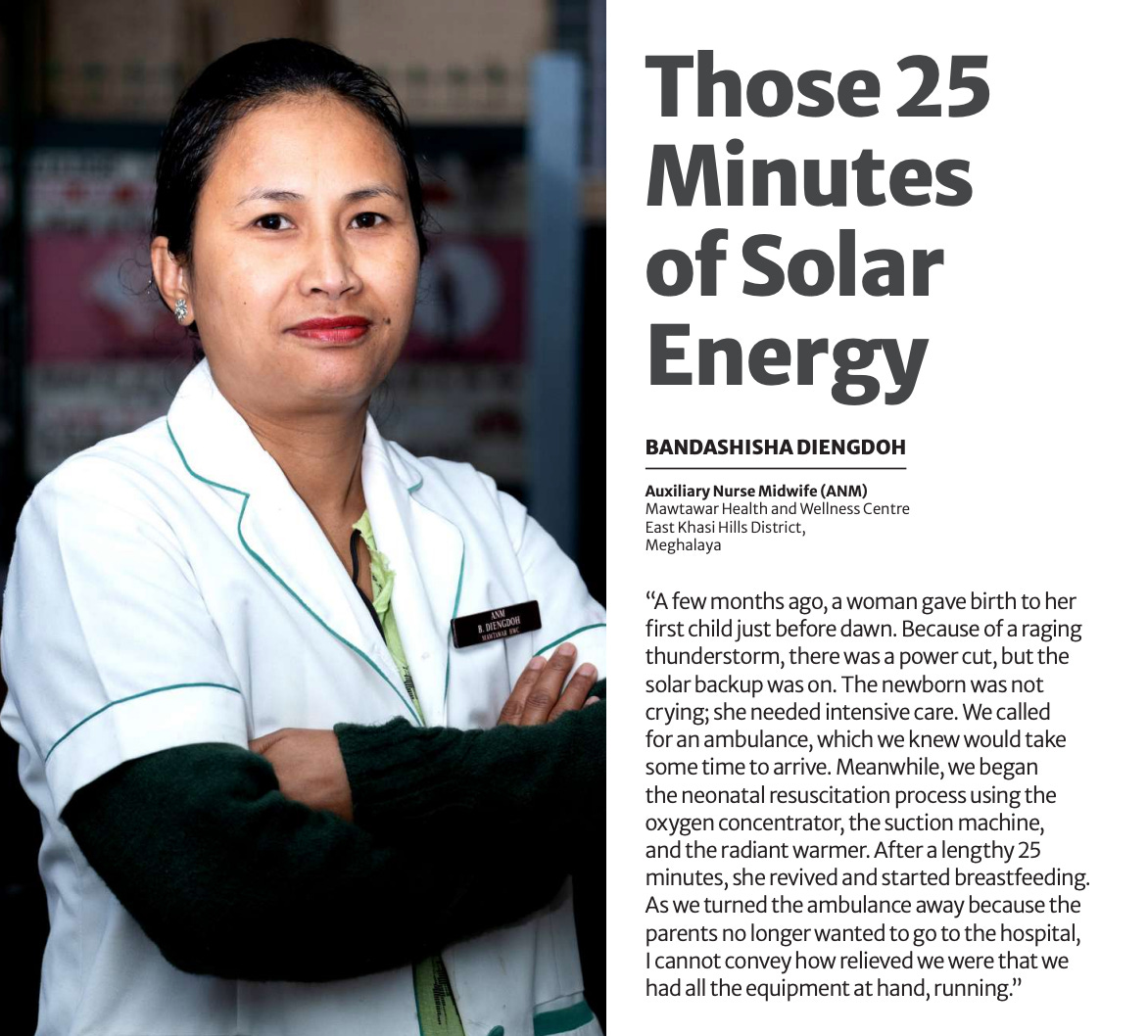

Power cuts were an everyday nightmare for the staff, Derifully Mawthoh, a caretaker at one of the PHCs in Meghalaya, in north-east India, says in a project report. “They had to deliver babies by candlelight and burn charcoal in portable stoves to keep the newborns warm. The arrival of solar energy makes it possible for them to use infant radiant warmers after every delivery. They can charge their phones and laptops… They can see the patients in a brightly lit room.”

Now, home deliveries have become rare, and mothers want institutional deliveries, says an auxiliary nurse midwife.

The solarisation programme is being carried out by SELCO, supported by IKEA and local governments, for immense, immediate benefits. In the last decade, the project has scaled impressively, from 15 PHCs in 2016 to 10,000 today, and targeting 25,000 by next year.

Scaling this can help the planet, with the health sector accounting for an estimated 5% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions globally.

Climate action empowering women?

In Bahraich, a district of UP, a middle-aged woman, Kusum, gave feedback on development programmes that are being tried out in her village. Her ask? Small tools to help maintain the machines provided under the programme. Machines like a battery-operated sprayer on a wheelbarrow-type vehicle. The machine means no more carrying heavy equipment on your back and no fossil fuel emissions.

Or take Ruby, a university student in UP’s Barabanki district. She’s working along with her studies, running a soil health diagnostic test for farmers. The test has been developed by Soil Doctor, a startup based in Delhi; the test is reliable, affordable, rapid and portable making it easy choice for farmers.

This test provides data on nutrients in about 30-60 minutes, compared to the many months by the earlier testing method, according to the Social Alpha team supporting the programme. This means the data is now actionable for the farmer in time for the current crop rather than after harvesting, when it’s too late. The cost is an affordable INR 200 or so.

Climate tech win-wins

Nearby, in another village, Sita Devi proudly shows how the biogas plant she and her husband have installed outside their house works. They put in a mix of cow manure and water and get cooking gas piped to their stove. This drastically cuts indoor air pollution compared to burning biomass. It also provides nutrient-rich slurry for their crops. And if there’s sufficient supply, she lets her neighbours cook with the smokeless fuel. She paid about INR 8,000, while the bulk was supported by development programmes.

Another role model is Rajendra Tudu, in a remote corner of Jharkhand’s Hazaribag district. His life changed thanks to a development programme and funding coming together and creating a pilot project which he joined. It trained and provided him with equipment such as a polyhouse and soil monitors linked to satellites. He went from being a migrant worker in far-off Mumbai washing dishes for a daily wage to becoming an agri-entrepreneur with an annual income of lakhs of rupees. His core business is cultivating and selling seedlings of cash crops to farmers.

In cities like Ahmedabad, Mahila Housing Trust (MHT), an NGO, has been researching and rolling out low-cost cooling solutions. With rising temperatures, keeping millions of people cool in our cities is rapidly becoming a major challenge. The latest MHT innovation this summer was a ‘cool bus stop’ which uses a high-pressure mist and curtains of grass to reduce extreme heat at bus stops by a few degrees. It was designed as net-zero with solar power. The idea has caught the imagination of officials in several other cities.

This follows MHT’s other project has been focusing on painting roofs white, the ‘cool roof’ project. These are mainly at houses whose residents cannot afford air conditioners or coolers. This technique can bring the temperature down by about 2-6°.

Solar power gains

Then there’s solar power at a more localised level. From Barabanki in UP to Hazaribag in Jharkhand, its value proposition is hard to ignore.

Saving INR 100 (about $1.17) is hard, says Ram Tilak. Yet he found it worthwhile to invest INR 50,000 for a solar-powered pump; the rest, the bulk of the cost, is subsidised through various funding options like philanthropy, CSR and others.

It saves him the cost and stress of hiring a diesel generator, buying fuel, buying a connection to the grid, which can be unreliable, and ensuring the timely availability of both to irrigate his crops. It saves the planet from GHG emissions. Sometimes he has excess capacity for neighbours to irrigate their fields.

But Veena Devi, an agri-entrepreneur in Hazaribagh, was open to solar but tilting towards a diesel genset only because it was quicker to get up and running. She needed power for a temperature-controlled polyhouse she built, particularly for grafted seedlings, which are very delicate. The choice in such cases is obviously solar, but access wasn’t easy. The priority now ought to be on how to ensure climate action funds and delivery systems are available to help people like her.

Gaps in climate action

While many of the examples above are encouraging, gaps remain.

The health centre project appears to be on track to solarise 25,000 PHCs. But there are well over 200,000 of these in India. As of now, there’s no plan in sight for those. The funds required for each is a fairly reasonable $3-4,000, but where will the funding and systems for so many come from?

Sita Devi is the only one in her village who has a biogas plant (with a superior, leak-proof tech.) Similarly, Ram Tilak is the only individual in that village to have bought a solar-powered plant. The low-cost climate tech has proved its value. How can the programmes that helped them be expanded to help others, and what are the hurdles?

Kusum’s demand for small tools for their agri-machines remains unmet, as last heard. What will it take for industrial centres in Haryana, Maharashtra, and Tamil Nadu to even hear of such demands, let alone address them?

In Ahmedabad, the first cool bus stop cost about INR 350,000 or a little over $4,000, mainly to install solar power for the mist machines. But even that was too high to roll out at all the bus stops they targeted, the MHT’s chief said recently at the World Health Summit in Delhi.

White paint on roofs requires high maintenance, according to a recent study by Chintan, another NGO. It found that in a cohort of 200 households in Delhi, not even a single painted cool roof was in good condition a year later, with ‘good’ defined as almost fully white as initially applied. The most effective reduction showed an impressive 13° temperature difference between a cool roof and a no-cool roof, but that was by using a mix of tarpaulin, existing tin, insulation sheet, cardboard, bamboo and jute.

Open to behaviour change

Innovations and new training are all very well, but the inflection point in several cases comes when communities see transparency in practice and value. Melinda Gates recounts a case in Shivgarh, UP, where women overcame the stigma attached to modern delivery practices once they saw or heard about the first case - a newly trained health worker, about 20 years old, saved a newborn by monitoring his temperature and providing body warmth. It got people talking and wanting this level of care for their babies.

Each innovation or adoption of a sustainable practice is likely to vary from case to case. A common thread is that such actions have shown the ability and eagerness of individuals and communities for behavioural change.

However, rather than remaining proof-of-concepts or one-offs, these need significant investment and sustained policy support to accelerate impact.

It’s a win-win, benefiting individuals, communities, and the country as a whole, moving towards sustainable growth. [This progress at the grassroots, however, must be accompanied by macro-level shifts, particularly the reduction of fossil fuel emissions. India’s GHG emissions have risen, with 72% of CO2 emissions from coal combustion alone.]

A significant hurdle is that much of this work is inaccessible to wider audiences, as these are often far from the major cities or influential policy, business and media circles. Many innovations and projects suffer an out-of-sight, out-of-mind fate.

This awareness gap needs to be narrowed to accelerate climate action.

Excellent piece! An eye opener about the green shoots of change.