Writing’s on the Wall: Timely Volume on India’s Coal Dilemma

Released between G20 and COP28, a new book looks at the role of coal in India's Just Energy Transition. Here's why it's a good read for ESG investors, sustainability officers, policy makers

The writing’s on the wall, warns a timely new book on India’s coal dilemma. The volume by multiple authors is focused on examining pathways to the single biggest course correction for global warming - decarbonisation - and how this can work in India given the “entire economic system is locked into” coal specifically as well as other fossil fuel–based energy and transportation systems.

‘The Role of Coal in a Sustainable Energy Mix for India’ is may not quite be for the mass market, yet it is a valuable read for anyone concerned with decarbonisation and a just transition to clean ‘green’ energy particularly policy makers, funders, businesses and investors and politicians too.

While more and more people are demanding climate action from their leaders, right at the start the editors, Mritiunjoy Mohanty and Runa Sarkar, write that the transition will be driven largely by policy rather than pulled by demand.

Addressing a Lack of Clarity

They point out that while the Indian government has set goals and announced targets towards a low carbon future, and made some progress in that direction, there still remains a lack of clarity on both the path and the means of achieving these.

Rather than look at India’s transition only from a top-down point of view, the 21-chapter book offers holistic insights. From emphasising a focus on people most affected from the grassroots (panchayat) level upwards to what the government can do in absorbing risks to meet the needs of transition finance. It is rich in data and also lists useful case studies to illustrate opportunities for all stakeholders.

‘Our Lives Revolve Around Coal’ But Ready to Ditch it

One of the chapters approaches the energy transition from the point of view of panchayats in Jharkhand. The eastern state has about 27% of India’s coal reserves and 8% of its revenues are from coal-mining taxes and royalties. But there’s a whole informal sector around it as well. A panchayat member says, “Our area is only coal – we cannot do without coal. Our lives revolve around coal.”

Three panchayats told the authors that 99% of the families are involved in the coal trade but earn only about 500 rupees a day, lower than the minimum wages. They collect coal, transport it on cycles and sell it to businesses such as restaurants. It is illegal but there are few other means of survival and authorities largely turn a blind eye, the book says. Closing the mines will hit them hard, but some of the respondents said that in case of better livelihood options, they would gladly give up their dependence on coal.

Free Coal Power vs Costly Solar

Initiatives to move communities away from the coal economy may not be effective. Renewables, especially solar-powered lights and water pumps are being promoted by various agencies such as Corporate Social Responsibilities (CSR) divisions of mining companies, civil society organisations, and by the state government. But as an elected leader pointed out that electricity at homes in most of the coal-field areas is free, while they will have to buy batteries and solar equipment if they need to switch.

A Kerala Village’s Success Story

In contrast, a small Kerala coastal village, Perinjanam, has installed a 1.16 MW rooftop solar power system across 700+ households in the panchayat. There are substantial gains: it’s saved over 1,300 tonnes of CO2 emissions, provided jobs to local youth, shown that a decentralised renewable energy (RE) project can be financially viable. Efforts are on to replicate this across over 900 gram panchayats in Kerala. A key ingredient, the authors point out, is political will.

A Business Case for CSV - Creating Shared Value

On a large scale, however, the transition needs to address how to tackle power plants fired by coal and other fossil fuels. The authors of the chapter, “International Experiences” delve into an alternative to the CSR called Creating Shared Value (CSV). As opposed to the government-mandated annual CSR compliances which depend on factors such as a corporation's profit, CSV is described as a systematic framework for collaborating with stakeholders across the life cycle of an asset right from the start to decommissioning. The example given is of Enel, an Italian multinational energy conglomerate.

In Chile, for instance, Enel operates a wind power project and trains local communities to manage it as well as create a tourist route to highlight the natural and cultural heritage of the area; in South Africa, Enel trains local young people as service technicians to match the skill demand at renewable energy plants.

The authors say the uniqueness of the CSV model is that it facilitates an open engagement between Enel and local communities on an ongoing basis. The potential for a similar approach in India is tremendous.

This focus on sustainable practices has a business pay-off in ways that CSR, which is viewed as a cost, may not be able to match. It helps in brand building, enhances reputation globally, and attracts ESG-aligned investors. Enel, a pioneer in sustainable finance, issued the world’s first sustainability-linked bond in 2019. Today, 55% of the company’s finance is through sustainable sources, which Enel plans to scale up to 70% by 2030.

India’s Coal Giants

It’s a model worth considering in India at a time when fossil fuel giants such as the government’s Coal India Limited (CIL, the world’s largest coal company) and National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC) are diversifying into RE.

While India has set an ambitious target to increase RE to about 50% in its energy mix by 2030, its use of coal will be going up. There are currently 27 GW of thermal power plants under construction and it will be burning more coal - not lesser amounts - over the next few years. The book estimates that there is likely to be more than a 50% surplus capacity for the foreseeable demand, “presumably” to account for delays, termination or withdrawal of coal mines once allocated as has happened in the past. Many energy experts in India such as Vibhuti Garg, Sunil Dahiya and Alexander Hogeveen Rutter have argued that investment into RE needs to be far higher than what it is currently, that RE is cheaper and a better business bet than coal can ever be now.

Social Cost for India

The social cost of coal, emissions and global warming in India is undeniable, one estimate puts India’s cost at the highest in the world [see here and here].

India’s stand has, rightly, been to demand equitable growth. The rich, developed countries are most responsible for historical accumulated emissions, and now developing nations are demanding that the Global North sharply reduces emissions this decade and allow the Global South its fair share of the remaining carbon budget. Neither access to finance nor to clean tech has been readily forthcoming from the developed nations to the Global South.

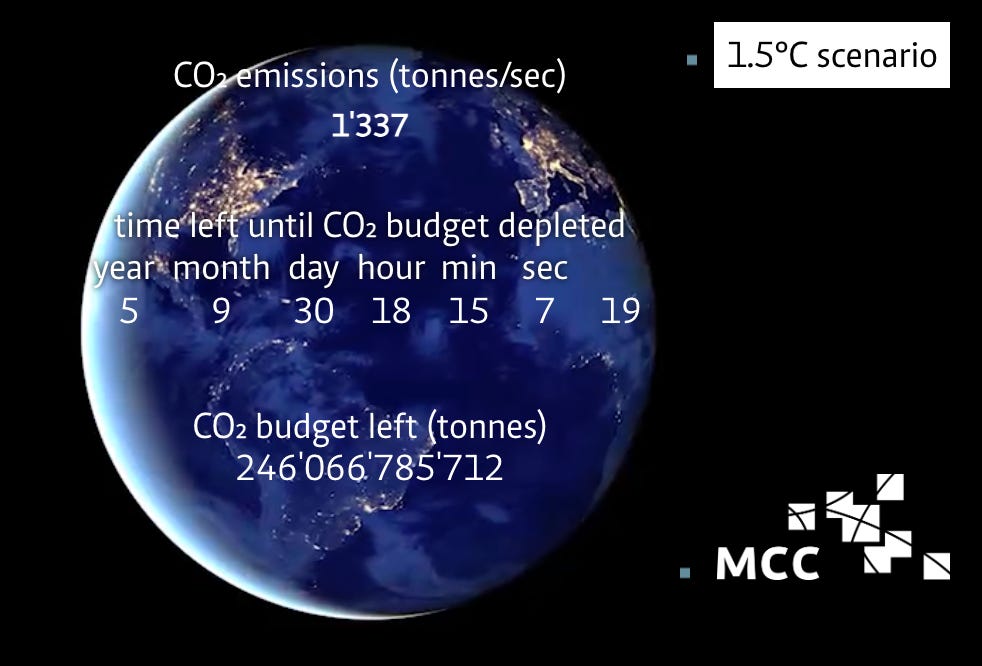

The carbon budget is an estimate in tonnes of emissions by scientists to 1.5°C global warming above the average temperature 150 years ago, when societies in Europe and America particularly started burning coal on an industrial scale. That budget is estimated at about 25 gigatonnes, and this year’s emissions are likely to be 40 GT of C02 equivalent (or GT CO2 eq).

India’s Dilemma

While India’s stand may be morally right and vital for rapid growth, but practically it remains one of the most vulnerable to global warming. Emissions can hurt its population and economy regardless of where the coal and other fossil fuel is burnt. The writing is on the wall.

Thanks for the shout-out!

It is definitely clear that as a growing economy with energy consumption at 1/3 the global average, India's electricity supply must grow massively to meet the burgeoning demand. However, I think the "dilemma" is false in that it assumes coal is cheaper/more reliable than RE. This was true 10 years ago, but is simply not true today. (https://energywithalex.wordpress.com/2023/06/17/why-is-coal-re-so-much-more-expensive-than-storage-re/)

Thanks for sharing the "CSV" model, which I hope can be applied in India. That said, Renewable is already creating thousands of jobs and livelihoods in India today. While we certainly need to be concerned about the just transition for mining-dependent districts, the overall economic opportunities provided by lower-cost power, cleaner air and water (boosting agriculture incomes) and reallocation of capital outweigh the social costs.