New Report Questions Efficacy of India's Clean Air Programme

Meteorological factors clean India's air a lot. Some policy action is working, like Ujjwala and replacing diesel transit. But climate change can worsen India's air pollution, the study warns.

A new study raises questions over the effectiveness of India’s flagship air quality policy, the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP). The study essentially makes two points.

One, a significant part of the recent improvement in pollution in the cities analysed was a result of the weather, factors like wind and rain which wash away pollutants.

Two, it warns that climate change may reduce such meteorological benefits in the future. That means pollution levels could worsen unless sources of pollution are rapidly eliminated.

The authors of the study published in Nature Sustainability, who are from Princeton University in the US and the University of Reading in the UK, reported a trend of rising pollution.

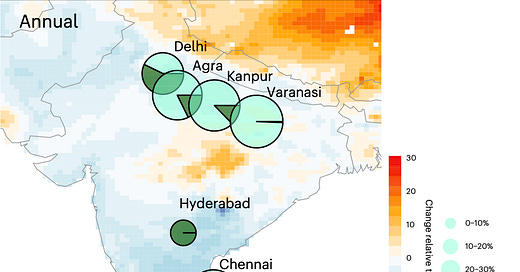

The study analysed six cities for which they had data across several years. The percentage contribution of favorable meteorological conditions to the observed air quality improvement was 57% in Delhi, in Chennai 18%, Hyderabad 100%, Agra 18%, Kanpur 13%, and Varanasi 1%.

Need for NCAP course-correction

The report evaluates the efficacy of the NCAP. It finds an 8.8% per year decrease in annual PM 2.5 pollution in the six cities with continuous air pollution monitoring since 2017.

Four of these six cities achieved over 20% reductions in PM 2.5 pollution by 2022 relative to 2017, thereby meeting the NCAP target.

However, the authors say that they found that ∼30% of the annual PM2.5 air quality improvements, and approximately half of the reductions during the heavily polluted winter months, can be attributed to favourable meteorological conditions that are unlikely to persist as the climate warms.

The lead author, Yuanyu Xie, Ph.D, is an Associate Research Scholar at the Princeton School for Public and International Affairs. She told me over an email interview that, “Our analysis, based on satellite and surface measurements, shows increasing emissions of PM (particulate matter) precursors (e.g., SO2, NOx). If this increasing trend continues, it may become more challenging for India to achieve the updated NCAP target by 2026, even with favorable meteorological conditions.”

Reports by a powerful government body, the Commission for Air Quality Management (CAQM) reflect how meteorological conditions affect pollution. It can be both “favourable,” and “adverse,” as was seen in November 2023.

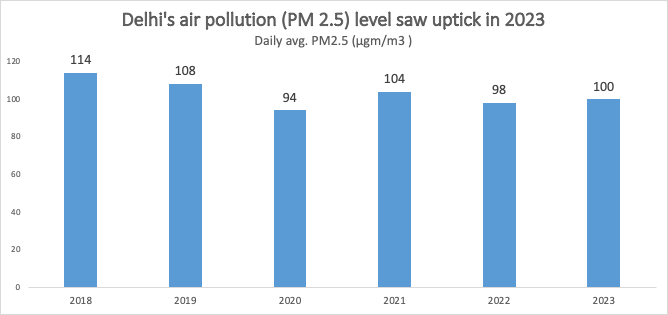

The CAQM’s data shows that the annual average concentration of PM 2.5 crept up last year to 100 micrograms/cubic metre, which is 20 times the WHO’s safe limit.

[PM 2.5 is an ultrafine particulate matter of a diameter of 2.5 microns or a fraction of a human hair’s width; it’s usually the most commonly tracked pollutant and has lethal health effects ranging from chronic lung disease, lung cancer to heart attacks, strokes and even depression and dementia.]

The agency often insists that air quality is improving thanks to policy interventions. “Continual and concerted efforts of all the stakeholders round the year also in 2023 have further helped to improve the general air quality parameters in Delhi as compared to the past few years…” In light of new scientific studies, this needs to be continually scrutinised to improve policy action.

What is working

For the years before 2023, the authors say, “We found slight decreases in emissions of primary particles but little change or increases in emissions of key PM2.5 precursors since the NCAP baseline year 2017.” PM 2.5 can be a toxic cocktail of several chemicals particularly key ones like sulphur dioxide (emitted by coal-fired power plants), nitrogen oxide (largely from vehicular emissions), and ammonia.

The decrease in PM 2.5 the study says is “driven in part by the success of the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana” launched in 2016. The Ujjwala scheme provides subsidised cooking gas connections to help replace solid fuel in poor rural households in India. In four cities, surface carbon monoxide decreased over five years starting in 2018. “The rapid penetration of clean cooking fuel over the past several years may thus be one of the important drivers of the observed PM 2.5 air quality improvements since 2017,” the study notes.

It also says replacing diesel with compressed natural gas in the transport sector of cities has led to “reductions” in black carbon emissions; with the rollout of more electric buses, this is likely to decrease further. Black carbon is considered a super-pollutant, with a short-term lifespan but is lethal.

How climate change can worsen India’s air pollution

A part of the Nature Sustainability study’s prognosis is graver. It spells out a potential link between climate change and worsening air pollution. Global warming has been known to disrupt a weather phenomenon known as Western Disturbances which brings rain and wind in North India, especially in peak pollution months. If there are fewer or no Western Disturbances that is likely to increase the concentration of pollution.

Yuanyu says, “We highlight that the observed improvements in PM air quality are partly due to favorable meteorological conditions, such as more frequent western disturbances. However, with increasing global surface temperatures driven by rising greenhouse gas emissions, the frequency of western disturbances is projected to decrease. Our study underscores that favorable meteorological conditions are unlikely to play a major role in the future, and substantial emission reductions will be necessary to bring India’s air quality to healthier levels.”

Many experts increasingly see fighting climate change and air pollution as one battle, given how closely these are interlinked. Reducing greenhouse emissions and non-GHG pollutants is a win-win strategy they advocate.

[Recent disasters like the landslide in Wayanad, Kerala, and spells of extreme rainfall in several parts of the country have shown the effects of climate change.]

$$$ benefits of reducing air pollution

The Princeton and University of Reading authors chose India for multiple reasons but essentially because of the severity of the crisis which they mention has an economic cost of $36.8 billion for just Delhi alone because of the years of life expectancy lost due to air pollution.

“India faces some of the most severe air pollution in the world. In 2023, nine out of the ten most polluted cities globally were located in India. Severe surface air pollution was estimated to be responsible for 1.67 million premature mortalities in India in 2019, approximately 8 years of life expectancy lost for 248 million residents of northern India (Delhi) with a resulting economic cost of $36.8 billion,” Yuanyu explains.

The challenge is to balance emissions and the need to pull millions out of extreme poverty in India and other parts of the Global South, a challenge which has raised issues of climate justice as the rich countries have developed far quicker by using up way more than their share of the carbon budget.

The authors say that India, along with other developing countries in the Global South, faces dual challenges in the coming decades as fast-growing populations and increasing energy consumption risk dramatically increasing the emission of air pollutants and greenhouse gases. They call for “strong policy intervention” without which rising pollution emissions and feedback effects from a warming climate—such as heatwaves, wildfires, and atmospheric stagnation—will impose a significant health burden on the growing and aging population.

This work highlights the need for substantial additional mitigation measures beyond current NCAP policies to improve air quality in India. - Nature Sustainability, July 2024

PM 2.5 linked to deaths

The Nature Sustainability report comes on the heels of a Lancet study done by Delhi-based Sustainable Futures Collaborative, the Institute of Environmental Medicine in Sweden, and Benaras Hindu University in Varanasi among others.

The report shows how air pollution is a severe health crisis. It is linked to thousands of deaths even in non-peak pollution months. Researchers found that 7.2% (or approximately 33,000) of all deaths each year across 10 cities could be linked to short-term PM 2.5 exposure higher than the World Health Organization (WHO) guideline of 15 micrograms/cubic metre (µg/m³).

Contrary to popular perception, the study found that the risk of death rises significantly with short-term increases in pollution; this is even in cities like Shimla, Chennai, and Bengaluru often seen as clean.

Evidence such as these should be studied closely by policymakers and officials, including ministers. It has implications for how the National Clean Air Policy (NCAP) should change.

The more things change…

‘The more things change the more they stay the same’ need not be the resigned adage for those pursuing better air quality in India. Pollution levels have stayed roughly constant for several years in places like Delhi, deteriorated in others like Mumbai, and improved in a few like Varanasi.

But if there was ever a time to step up the battle against air pollution in India, seen as one of the world’s most polluted regions, it is now. A new parliament, seeds of bipartisan support, strong new scientific evidence, and a chance to overhaul NCAP which has completed half a decade.

The central and state governments in India have a chance to deliver results, building on the successes and setbacks of recent policies. Most crucially scientific evidence essentially makes the case for cutting emissions ASAP.