Delhi Pollution Doubles in November vs. October, 'Faulty' Fire-count Shakes Officials

A landmark moment in north India’s battle for air quality. Delhi suffered the worst pollution in 8 years. A controversy over wrongly counting thousands of farm fires has erupted.

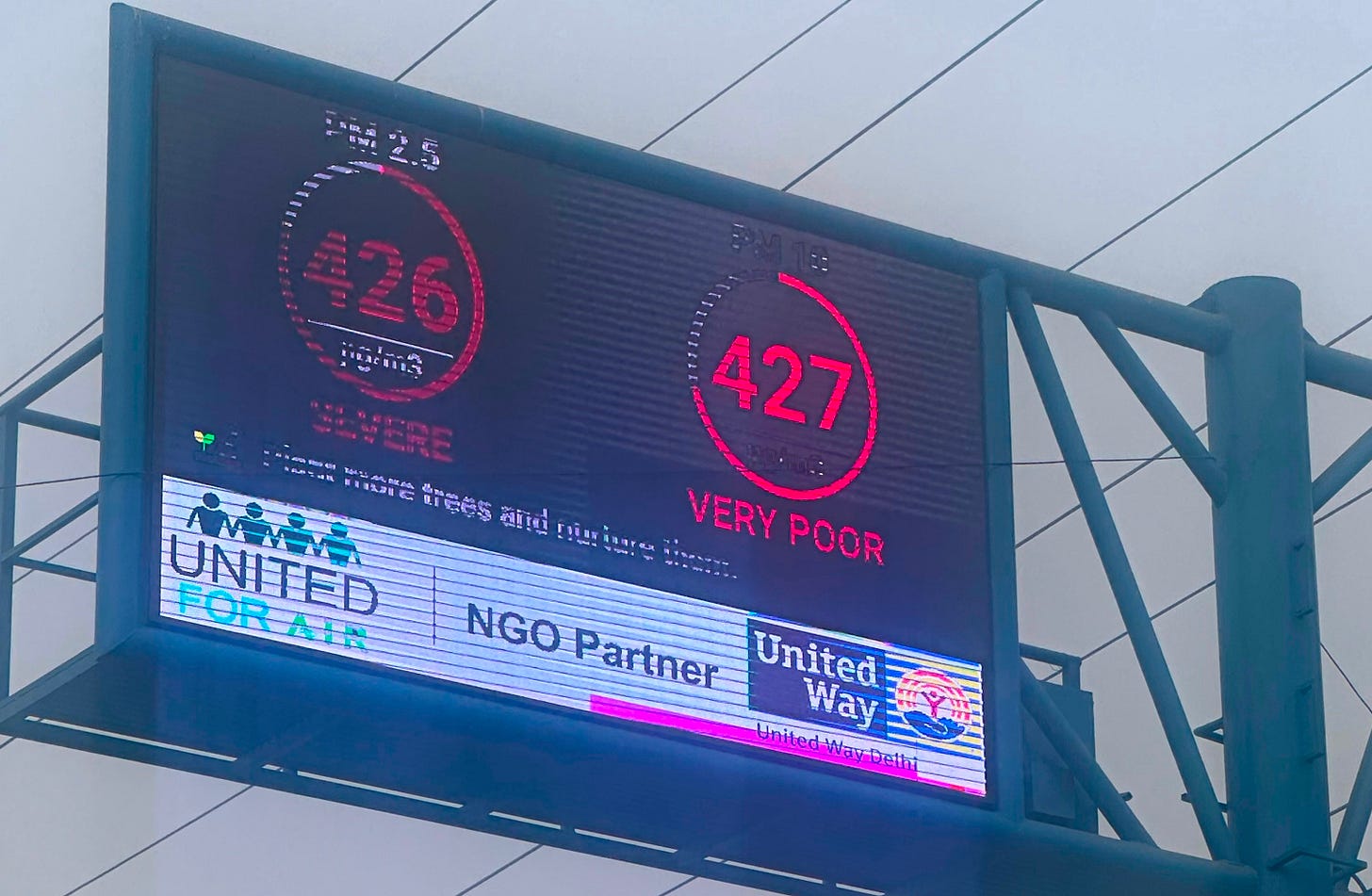

A big electronic signboard in the heart of Gurgaon shows the current PM 2.5 level as 426 micrograms/cubic metre; the day’s average should ideally be 15 as per WHO.

Beneath the sign, it’s business as usual. Crowds on the street, few if any wearing masks. Heavy traffic with some vehicles spewing smoke. The sunlight’s a hazy brown discoloured by PM 2.5, a very toxic particulate matter of a microscopic size, 2.5 micrometers or less.

Delhi and its neighbours are suffering the worst phase of air pollution in years and “the children are breathing toxic air” the Supreme Court was informed by a lawyer assisting it on the matter. The average PM 2.5 level shot up from 111 in October to 270 micrograms/cubic metre in November, till the 22nd, as per a research organisation, CREA.

To cut through the mix of science, data, health, court hearings, and politics here is a summary of some key developments in the past few weeks.

It’s been a significant pollution season for several reasons, not least because pollution has bounced back - it’s the worst in eight years.

However, the biggest reason is a suspected undercount of the stubble fires in two states north of Delhi. These are fires started by farmers to clear their fields of paddy stubble.

New evidence suggests stubble fires have not been falling drastically

A significant source of pollution in November is the burning of paddy stubble in the two states, Punjab and Haryana. For the past couple of years, official data has maintained those fires have fallen drastically - about 60% in Punjab and 69% in Haryana (see chart below).

It turns out that the drastic fall in the fire count may not be correct.

Scientists and the Press have exposed enough evidence to warrant an independent investigation into the undercount. These fires are a significant source of pollution at this time of the year, worsening the air pollution health crisis.

Many fires appear to be lit late afternoon after two satellites used for counting have crossed the region. Hiren Jethva, a NASA scientist, first raised this and was supported by other researchers and The Tribune’s ground reports.

The Supreme Court called this “very disturbing” and directed ISRO (India’s space agency) to get data from geostationary satellites so that there’s 24-hour coverage. The Commission for Air Quality Management (CAQM), operated by the Central government, has repeatedly maintained in court that the number of fires has fallen. The CAQM, formed by an Act of Parliament, is powerful and has the unique mandate to follow an airshed approach i.e. act in multiple states regardless of political boundaries.

However, The Hindu reported that the CAQM knew that farmers were burning stubble after the satellite over-pass and that the burnt area had increased. Following this report, the court sought the minutes of the meetings and directed ISRO to work out a way of monitoring the fire count accurately.

Some farmers even told The Hindu that a government official had asked them to light fires after 4 pm.

Outrage over 10,000 fires in Oct-Nov, but not for ~30,000 fires Jan-Aug

For a moment, set aside the fire undercount controversy. Much of the outrage in various media over the winter pollution is directed at the farm fires in Punjab and Haryana.

This year, the official count of stubble fires from 1st October to 19th November in the two states was under 10,000 (see chart below). The fires contribute to about a third or more of daily PM 2.5 pollution in Delhi according to the IITM; the contribution varies depending on the number of fires, wind direction and temperature.

Compared to these ~10,000 fires, there were over 29,000 fires detected between January to August 2024. This is the highest in five years for both Punjab and Haryana, as per an analysis by Climate Trends a Delhi-based group.

Yet there’s little to no discussion in the mainstream Press or influential sections of social media about the summer fires. This pollution, mainly in the hotter months, may not be as bad as in winter because of climatic conditions, but it needs to be addressed at par with the October-November fires.

True, winter in the north has a few more sources of pollution (mainly farm fires and fires to keep warm) but most major air pollution sources like industry, vehicles, construction & demolition and waste are 365x24x7. Yet, the outrage is seasonal.

CAQM has the power so why doesn’t it use it more effectively?

This season’s crisis has also led the Supreme Court to push the CAQM to be more proactive. On 18th November it pulled up the commission for delaying action and waiting for the AQI to improve was “completely a wrong approach.” The message appears to have hit home.

Two days later, in a snap, the CAQM made it mandatory to shut schools in five cities, Delhi and its next-door neighbours. Till now, this had been an advisory to local administrations. The question is, why did it not exercise this power all these years? And going ahead, can it intervene more decisively especially to cut pollution at source?

While on the sensitive topic of protecting school-going children, one of GRAP’s failings is that the stage to shut down schools comes very late, when PM 2.5 is over 250 micrograms/cubic metre, and AQI is 400+. [GRAP is the graded response action plan.]

Research has shown the health risks are high at far lower levels; some doctors advise keeping children indoors when the AQI is 150, which it hasn’t been for weeks now. So, what is the plan to protect school kids at these lower but still harmful level of pollution?

[Note: Closing schools is a complex argument, with low-income families against it as argued in the Supreme Court.]

Pollution from thermal power plants more than farm fires

A recent CREA report stated that thermal power plants (TPPs) emit particulate matter over 10 times more than stubble fires in Punjab and Haryana and 240 times higher sulphur dioxide. This SO2 affects the lungs in several ways - wheezing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness especially during exercise or physical activity, whereas long-term exposure reduces the ability of the lungs to function.

In November 2021, the CAQM had temporarily shut down six coal-fired power plants the Delhi-NCR in an emergency move to cut air pollution. Should that be considered now in 2024 as well?

[Note: Read here why Niti Aayog now advises against the 2015 plan to cut emissions from TPPs.]

Cutting trees for flyovers: More vehicular pollution?

Officials in charge of the city appear to be pursuing policies favouring vehicles even though these contribute most to Delhi’s air pollution, a staggering 47% according to one study.

Yet, despite Delhi’s air pollution, public transit and urban heat problems, trees continue to be targeted by local authorities for new roads. In the last few days, the Delhi High Court criticised a move to cut trees for a flyover.

Two years ago, the CAQM’s report, Policy to Curb Air Pollution, showed that over 70% of the population in Delhi-NCR travels by public transport, walking, cycling, autorickshws, and trains. This, the report said, is an opportunity for clean air gains in the region.

Instead, since that 2022 report, the number of vehicles in Delhi has gone up from 13.5 million to 15 million now.

Pseudo-science persists in peak pollution

The headline-grabbing pollution has oddly enough put some political rivals on the same side of the fence.

In recent weeks, two high-level leaders - one, the Centre’s Lt. Governor and the other a minister of the Delhi government have backed steps dismissed by scientists. Delhi’s LG launched mist machines on streets pitching these as anti-smog. The minister went further (or higher!) and has called for cloud seeding; Delhi’s air is usually the cleanest when it rains heavily or is very windy.

Smog towers, cloud seeding or sprinkling is not effective because pollution in and around Delhi is a thick layer, and these measures can’t control it, IITM’s Dr Sachin Ghude said at the India Clean Air Summit in Bengaluru.

Government and external scientists have repeatedly pointed out that steps like sprinkling, smog towers and cloud seeding cannot control Delhi’s air pollution. The layer of pollution is too thick.

What India’s environment minister says on air pollution

India’s environment minister, Mr Bhupinder Yadav, who’s been busy with the state elections in Maharashtra till a few days ago, finally spoke on the air pollution crisis. “November’s climatic condition poses a challenge to air quality in the Delhi-NCR area,” he said, while listing the steps the government has taken like the national clean air programme (NCAP), leapfrogging fuel standards from BS4 to BS6, affordable transportation, and so on.

Delhi’s winter air pollution has been extreme for over a decade now. The solutions and roadmaps are known both within and outside the government, but what’s missing is political will.

At this juncture, there’s a new opportunity and hope: India, like all other countries, has to provide its NDCs or nationally determined contributions - a list of their climate action promises - to the UN Climate Change. At COP29, global health experts called for air quality to be made part of the next NDC due in a few months.

Cutting pollution sources is a win-win for air quality and the planet, for our lungs and the economy.